SJC Will Decide When Forced Blood Draws Are Permissible and Admissible

Today, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) hears oral argument in Commonwealth v. Bohigian, a case that addresses, among other issues, when law enforcement can take a subject’s blood without consent and when evidence of that blood draw is admissible in court.

Today, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) hears oral argument in Commonwealth v. Bohigian, a case that addresses, among other issues, when law enforcement can take a subject’s blood without consent and when evidence of that blood draw is admissible in court.

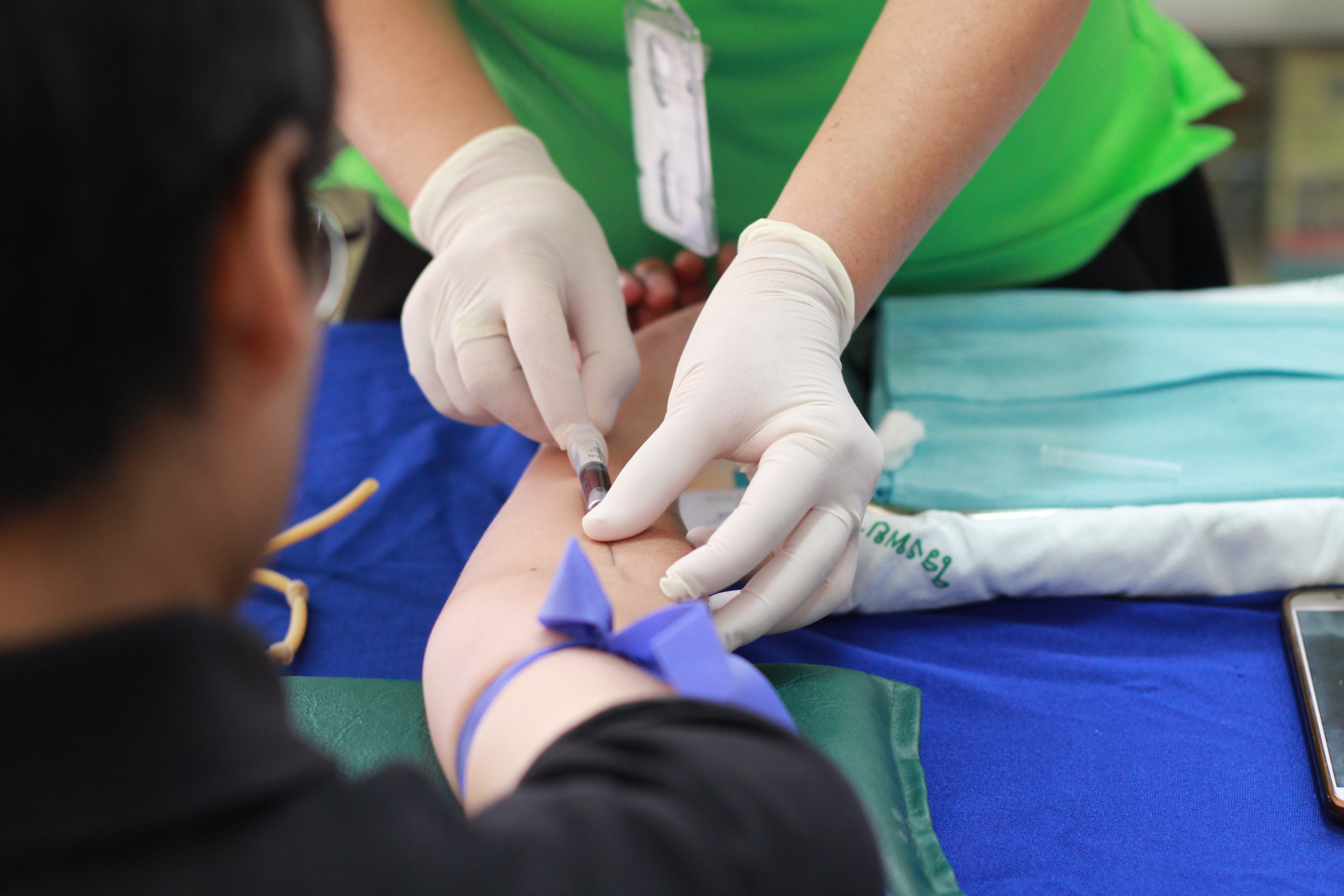

Mr. Bohigian was charged with operating under the influence and related crimes after a severe car accident. When Mr. Bohigian arrived at the hospital after the accident, police presented a nurse with a search warrant to draw his blood. Over Mr. Bohigian’s objection and at the instruction of a police officer, the nurse drew Mr. Bohigian’s blood. The results of the blood test indicated that Mr. Bohigian’s Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) was over the legal limit at the time of the accident.

Mr. Bohigian moved to suppress the blood test evidence results on two grounds. He argued that the blood draw itself was impermissible, because in order to issue a search warrant requiring a forcible blood draw, a court would have to conduct an adversarial hearing and analyze certain factors. Mr. Bohigian also argued that admission of the blood test evidence violated a statute—G. L. c. 90, § 24(1)(e)—that permits BAC evidence from a chemical test to be admitted into evidence only if, for a test made by or at the direction of a police officer, the defendant consented to the test. The trial judge denied Mr. Bohigian’s motion to suppress.

Should the Blood Test Evidence Have Been Admitted?

The arguments about the admissibility of the evidence center on G. L. c. 90, § 24(1)(e). That provision states that blood test evidence “shall” be admissible, provided that if the test was made “by or at the direction of a police officer, it was made with the consent of the defendant.”

The trial judge found that this case did not fall under G. L. c. 90, § 24(1)(e), because the blood draw here occurred pursuant to a duly authorized search warrant, and was thus not at the direction of a police officer, but of a court. Mr. Bohigian argues this conclusion wrongly ignores Massachusetts Appeals Court precedent holding that the statute excludes blood tests taken without the defendant’s consent at the direction of any state actor. The facts of the case also support Mr. Bohigian’s case even if the term “police officer” is read literally—the police officer made the decision to do the blood draw, drafted the warrant, drove it to a judge’s house to have it signed, then brought it to the hospital and directed the nurse to draw the blood.

The Commonwealth, on the other hand, argues that the statute is simply irrelevant to a situation in which the Commonwealth proceeds pursuant to a warrant rather than by trying to obtain the consent of the subject. In reply Mr. Bohigian points out the statute says nothing about search warrants and make no explicit exemption that waives the statutory consent requirement in the face of a search warrant.

Whether the Court is willing to affirm the Appeals Court’s reading of the statute that any state actor is prohibited from taking blood without consent, the facts of this case clearly support a finding that Mr. Bohigian’s blood draw was made by and at the direction of the police officer, and thus should have been deemed inadmissible.

Was the Blood Draw Permissible?

Relying on the SJC’s decision in Matter of Lavigne, Mr. Bohigian also argues that he was entitled to an adversarial hearing before the search warrant issued. In Lavigne, the SJC held that when the Commonwealth seeks a warrant to forcibly extract blood for a DNA test from someone not yet charged with a crime, the subject of the warrant is entitled to an adversarial hearing before the warrant may issue. The court reviewing the application must find that there is probable cause to believe both that the subject of the warrant committed the crime, and that the blood test would help in the investigation of that crime. In addition to making the probable cause determination, under Lavigne a court must also weigh a set of factors: (1) the seriousness of the crime; (2) the importance of the evidence to the investigation; and (3) the unavailability of less intrusive means of obtaining the evidence against (4) the suspect’s constitutional right to be free from bodily intrusion.

Relying, in part, on a different SJC case, Commonwealth v. Miles, the Commonwealth argues that Lavigne does not control this situation because the evidence in question was “fleeting,” generating exigent circumstances that vitiate a subject’s right to a hearing before a search warrant is issued. In Miles the SJC denied a defendant’s challenge to a trial court order that he be inspected at a hospital for signs of poison ivy. The SJC indicated the temporary character of the physical evidence (signs of poison ivy) was relevant to its decision, but also noted that the exam the defendant was required to undergo was significantly less intrusive than a blood draw and that the defendant had waived his right to a hearing when he voluntarily went to the hospital for the examination. Mr. Bohigian argues that because a blood draw is much more invasive than a visual inspection of a subject’s body, he is entitled to greater procedural protections than the defendant received in Miles. In deciding whether a warrant must issue before a blood draw and the requirements for such a warrant, the SJC will therefore need to decide how to balance federal and state constitutional protections against unreasonable searches and seizures against law enforcement’s desire to obtain fleeting evidence.

The Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS – Massachusetts’ public defender organization) and the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (MACDL), authored an amicus brief on this point. Amici make an even broader argument than Mr. Bohigian, that G. L. c. 90, § 24(1) flatly prohibits blood draws without consent in all circumstances. The section amici rely on, § 24(1)(f)(1) imposes a presumption of consent to blood tests on anyone who drives in the Commonwealth, but states that if someone refuses a blood test, “no such test or analysis shall be made.” (Refusing to undergo a blood test carries with it a mandatory loss of license for at least 180 days.) Amici argue that this provision gives an OUI suspect the right to refuse to undergo a blood test whether or not the police secure a warrant.

If the SJC were to agree with amici on this point, it would obviate the need to determine when a warrant could issue for a blood draw, because there would never be a circumstance where such a warrant was necessary. Amici’s view would simplify the scheme for obtaining blood evidence: either the suspect gives consent, and the evidence can be collected, or she does not, and the Commonwealth cannot collect the evidence. Meanwhile, if the SJC were to agree with the Commonwealth on both points, it would grant the Commonwealth the power to make an end run around the requirements of G.L. c. 90, § 24(1)(e), and simply obtain a warrant, with no opportunity for the subject to be heard, any time the police wanted to obtain blood draw evidence.

The SJC decision could eliminate the need for a suspect’s consent or eliminate the ability of the Commonwealth to obviate consent by obtaining a warrant. I would hope that in wrestling with statutory language at issue and the technical procedures for obtaining blood draw evidence, the Court does not lose sight of the bigger picture—the importance of safeguarding the right to bodily integrity. By driving on the roads of the Commonwealth, a person should not have to agree to being strapped to a hospital bed against his will and have blood forcibly taken from his body at the direction of the state.

If you have been arrested or charged with an OUI and need an attorney, please call us at (617) 742-6020.

Boston Lawyer Blog

Boston Lawyer Blog